Did I ever mention that journalists are the best people in the world to hang out with? They are generally well-traveled and informed, much more so than most people, more so also than most other kinds of writers. And because they have seen so much, they are relaxed, they have developed a distance between themselves and what's going on. They have a good bullshit-detector. They take everything with a pinch of salt and a sense of humor. This way of seeing the world is far more grown-up than most other ways. They also know how to hold a conversation.

So I was glad to find out that the journalist Erica Fischer was among us, and, predictably, it is she I hung out with most. When she was younger, Erica was a diehard feminist, maybe even close to a militant feminist, in Vienna, where she grew up. When I took a look at her website (www.erica-fischer.de), which has a photo gallery of all the fantastic things she did, I realized how much she believed in what she did. She was really out there protesting, activating, working at creating a better world. I don’t think I've ever believed in anything enough to do something like that. Her passion and courage was overwhelming. I was impressed, and – I'm not ashamed to admit it – a little bit in love.

Now, she writes mainly about Jewish themes. She had a bestseller with "Aimee and Jaguar," the true story of a German woman and Jewish woman who fell in love during the Third Reich. I accompanied Erica to a theater where the film made from her book was shown and where she had a discussion afterwards. She was quickly surrounded by beautiful young women – lesbians - whose lives she had touched with that book. She wishes her book and the movie would have more effect on people in the sense of teaching them about the Holocaust than it does on young lesbians. But what she forgets is that people don’t write fan letters to authors who have opened their eyes to anti-Semitism. But the effect is still there.

Here at the Villa Guesthouse Erica finished her next book (her twelfth, I think), a very personal book about her relationship to her tyrannical mother and her troubled, suicidal brother in Vienna. She read a few pages to us: It is personal, intense, lyrical, powerful and fascinating, and I think there is potential here for a big success. I keep telling her that, but she doesn't believe me. But no one believes an American. She doesn’t believe me when I say Marx didn’t understand a thing about the economy, and I am right about that, so maybe I will be right about this, too.

Here are the first few pages:

Der Schmerz sticht zu wie ein Messer, ein starres Korsett umklammert Nacken und rechte Schulter. Ich kann den Hals nicht mehr drehen, Zurückschauen ist aussichtslos. Sogar das Atmen tut weh.

Zu spät. Das Telefon schrillt in Pauls Wohnung sechshundert Kilometer entfernt, dreimal, fünfmal, zehnmal. Die Wohnung ist klein, bis zum zweiten Klingelton ist der Flur von jeder Stelle aus zu erreichen. Dort steht das Telefon auf einem niedrigen Schränkchen, gleich neben der Eingangstür. Beim Telefonieren kann man sich im Spiegel sehen. Drei Schritte rechts das Bad mit dem Klo. Daneben die Kammer für den Staubsauger und die Urlaubskoffer.

Die Wohnung ist leer, ich kann es förmlich hören, der Klang der Klingel hohl. Dieses widerwärtige schwarze Telefon mit dem Schmutz unter der Wählscheibe. Der Hörer schwer und unhandlich. Wie oft habe ich ihnen gesagt, sie sollen ein neues Telefon bei der Post bestellen, es kostet nichts. Ein modernes Tastentelefon, mit dem man telefonieren kann, ohne sich den Finger zu verstauchen, neu, leicht und sauber. Doch alles Neue macht ihnen Angst.

Oder: Mein Bruder liegt röchelnd auf dem Bett, würde nicht abheben, auch wenn er noch könnte. So ist es schon einmal gewesen, vor zwanzig Jahren.

„Ruth, Paul röchelt!“ Die Stimme der Mutter am Telefon hysterisch. Sie wollte über Nacht wegbleiben und kam überraschend zurück. Er lag auf seinem schmalen Jugendbett im Kabinett und röchelte. Über ihm türmte sich seine Bibliothek. Die Dichter und Denker schauten teilnahmslos auf ihn hinunter.

„Mach kein Theater“, schnauzte ich die Mutter am Telefon an. Wenn sie Gefühle zeigte, wurde ich zu Eis. Dass sie es damals schaffte, die Rettung zu rufen, wundert mich heute noch. Wohin er gebracht wurde, ließ sie mich nicht wissen, ich musste es selbst herausfinden. Das hatte ich davon.

Im Spital klang Pauls Atem wie durch einen Lautsprecher verstärkt, Plastikschläuche überall, der Magen bereits ausgepumpt. Er warf den Kopf hin und her, und wenn er die Augen einen Schlitz weit öffnete, sah man nur das Weiße.

Es ist tief in der Nacht und plötzlich stiller als sonst. Meine Berliner Wohnung liegt an einer Pflasterstraße. Wenn ein Auto vorüber fährt, poltert es. Rund um meinen schmerzenden Hals ist die Welt erstarrt. Meine Stimme am Telefon klingt fremd, wie eine automatische Ansage. Die Kusine. Merkwürdig, dass ich in Wien tatsächlich eine Kusine habe, wir sind einander in der letzten Lebensphase meiner Mutter näher gekommen. Sie hat sich um sie gekümmert, und um Paul.

„Warten wir bis morgen“, bittet sie. Sie ist erkältet, und draußen türmt sich der Schnee. Doch warten kann ich nicht.

„Ich melde mich wieder.“

Das Kreischen des Telefons durchschneidet die Stille.

„Ja?“ Meine Stimme ist tonlos. Die Feuerwehr ist über die Balkontür eingestiegen, berichtet die Kusine, auch krank und um drei Uhr früh immer noch effizient.

„Wir werden ein neues Glas in die Balkontür einsetzen lassen müssen.“

Sie denkt immer an alles. Die Wohnung ist leer, sagt sie, mustergültig aufgeräumt. Auf dem Couchtisch ein Schlüsselbund, die Schlüssel passen in die Wohnungstür. Daneben drei beschriftete Kuverts. Sie hat nichts angerührt. Sie klingt erleichtert, eine aufgeräumte Wohnung ein Zeichen von Normalität. Gewiss ist sie froh, kein Blut vorgefunden zu haben, keinen am Fensterkreuz hängenden Paul, ja nicht einmal einen röchelnden Paul. Eine aufgeräumte Wohnung beruhigt.

Ich rufe eine andere Kusine an, in Sydney. Vorher überprüfe ich, welche Tageszeit dort ist. Auf keinen Fall will ich sie wegen einer Frage wecken, deren Antwort ich schon kenne. Meine englische Stimme klingt noch fremder. Noch nie habe ich mit Australien telefoniert. Wenn man in Wien aufgewachsen ist, telefoniert man nicht mit dem Ausland. Nein, Paul ist nicht hier, meldet die australische Kusine als ob sie die Frage nicht überraschte. Macht nichts, war nur so ein Gedanke gewesen.

Ein neues Leben in Australien beginnen, Pauls Traum. Oder in New York. Die Emigranten von damals haben es auch geschafft, sagte er. Sie kamen mit nichts und haben sich ein neues Leben aufgebaut.

„Damals gab es Hilfsorganisationen“, wandte ich ein, „du bist kein Flüchtling. Die Schoa ist vorüber. Das Leben in den Vereinigten Staaten ist hart. Wenn du es schon hier nicht schaffst, wie erst dort?“

Das war böse, das hätte ich nicht sagen sollen.

„Du weißt nicht, mit wem du es zu tun hast!“, blaffte er zurück.

Ich verstand. Immer diese Drohung, seit Jahrzehnten schon.

Als die australische Kusine und ihr Mann ein Jahr zuvor in Wien waren, ging ich mit Paul das Nachtmahl einkaufen. Meinl am Graben, das vornehmste Geschäft der Stadt. Er suchte die teuersten Sachen aus, Käse, Schinken, Lachs, Wein. Ich wollte ihn mäßigen. Die Familie hat immer sparsam gelebt, große Sprünge konnten sich unsere Eltern nicht erlauben. Nach dem Tod des Vaters war die Mutter stolz, mit der kleinen Pension so gut zu haushalten, dass immer noch Geld für den Urlaub blieb. Der Urlaub musste sein, seit den fünfziger Jahren fuhr die Familie jedes Jahr in den Urlaub, nach Italien, Jugoslawien, Griechenland. Für diesen Höhepunkt des Jahres musste man sich im Alltag einschränken. Und jetzt Meinl am Graben. Paul war wie im Rausch. Aufgeregt packte er immer mehr Köstlichkeiten in den Einkaufswagen.

„Es ist ja nur für dieses eine Mal“, sagte er.

Er sagte nicht „das letzte Mal“, das nicht. Aber es klang so.

I was in awe of her and I still am. She's a freelancer like I am and has the same kind of financial insecurities that I do. I asked her how she manages to deal with it and she shrugged and said, "I'll be working till the day I die. That's fine with me." That's courage.

Her prize: Best Friend.

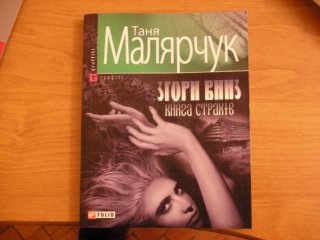

Tall and shy, Larysa wins the prize for Biggest Enigma. She levitated through the house like a ghost. She would appear in the kitchen late at night, nod and say "hello," one of the few English words she knew, and make tea, and then you would turn around and she was gone again. Leaving lots of speculation behind. Was she shy or did she just hates us all? I asked her to dance with me once – it happens once in a while when I am in a very good mood – but she declined, citing a cold.

Tall and shy, Larysa wins the prize for Biggest Enigma. She levitated through the house like a ghost. She would appear in the kitchen late at night, nod and say "hello," one of the few English words she knew, and make tea, and then you would turn around and she was gone again. Leaving lots of speculation behind. Was she shy or did she just hates us all? I asked her to dance with me once – it happens once in a while when I am in a very good mood – but she declined, citing a cold.  She tended to have breakfast around 2pm and dinner after midnight. One morning around 5am I came down to the kitchen to get coffee so I could wake up and found Larysa and Tanja, both being Ukrainian, wrapped up in conversation. But Tania refused later to tell us what it was about. On another occasion, she poured some kind of vodka into a pan and lit it on fire and served us all a warm, spicey drink. After she won the Nobel Prize wager (see below), she cooked us a heaping, steaming platter of Turkish rice-and-chicken-dish and thereafter would dare to come among us on some occasions and sit and drink or smoke and nod at certain points in the conversation. It was then we began to notice a beautiful smile.

She tended to have breakfast around 2pm and dinner after midnight. One morning around 5am I came down to the kitchen to get coffee so I could wake up and found Larysa and Tanja, both being Ukrainian, wrapped up in conversation. But Tania refused later to tell us what it was about. On another occasion, she poured some kind of vodka into a pan and lit it on fire and served us all a warm, spicey drink. After she won the Nobel Prize wager (see below), she cooked us a heaping, steaming platter of Turkish rice-and-chicken-dish and thereafter would dare to come among us on some occasions and sit and drink or smoke and nod at certain points in the conversation. It was then we began to notice a beautiful smile.  Larysa, it turns out, is a translator. I could not figure out what she translates, other than from the Polish into the Ukrainian, but I did learn that her husband is a famous Ukrainian poet and her daughter has already translated Stephen King short stories into Ukrainian. Somehow, both facts made her very cool. Here is a poem by her famous husband:

Larysa, it turns out, is a translator. I could not figure out what she translates, other than from the Polish into the Ukrainian, but I did learn that her husband is a famous Ukrainian poet and her daughter has already translated Stephen King short stories into Ukrainian. Somehow, both facts made her very cool. Here is a poem by her famous husband:

Unbeknownst to us, she was secretly famous in her own right. One day, Katja came back from an expedition into town and announced that she had seen Larysa outside the university surrounded by eager students. Apparently she had given a lecture there on translating, but when confronted directly about it, she admitted nothing, but instead only nodded and smiled and retreated into her room. Leaving us to speculate in an almost jealous, admiring way.

Unbeknownst to us, she was secretly famous in her own right. One day, Katja came back from an expedition into town and announced that she had seen Larysa outside the university surrounded by eager students. Apparently she had given a lecture there on translating, but when confronted directly about it, she admitted nothing, but instead only nodded and smiled and retreated into her room. Leaving us to speculate in an almost jealous, admiring way.