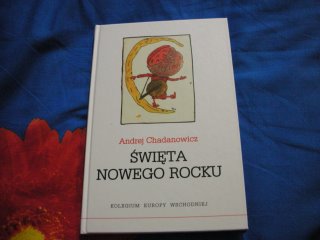

I've been trying for a while now to find out for sure how Mirek Nahacz died, why, and whether his fourth book is being published. But the Polish media seem to have dropped the story after the initial reports in July that is was suicide and besides, I can't read Polish, so the end of his story will remain closed to me as if it had happened on another planet, just as I will never know his books, which were never translated into English.

In the last days of July, they found his body in his apartment in Warsaw. Though I waited a while to find out more details and asked a Polish-speaking friend to comb the papers for additional news, all I could out was that the police believe it was suicide. I will probably never know more. The language barrier is complete. I will never know what happened; I will never know what happened to his girlfriend or speak to her; I will never know if his fourth book was published or will be published or if it worked out to be the masterpiece he wanted it to be.

I liked Mirek and I was jealous of him, too. I liked him because, from talking to him in his broken English, it seemed that he had a similar taste in literature as I did. He liked the American post-modernists; we were both fans of John Barth; he liked the beat generation more than I did, especially William Burroughs. I asked him about his new novel, the one he was working on – his fourth – and I liked what he said.

I liked Mirek and I was jealous of him, too. I liked him because, from talking to him in his broken English, it seemed that he had a similar taste in literature as I did. He liked the American post-modernists; we were both fans of John Barth; he liked the beat generation more than I did, especially William Burroughs. I asked him about his new novel, the one he was working on – his fourth – and I liked what he said. It was to be a science fiction novel with a real page-turning plot and written in a prose style with high literary standards. I too had always dreamed of that: combining the genre adventures I loved like Tolkien and Conan the Barbarian and all those things with a literary quality that lifted them up to the level of Shakespeare (after all – in a way, isn't that what Shakespeare did?). Though I could not read his books and never will be able to, I felt I was speaking with a kindred spirit. And I felt that perhaps he would succeed. That gave me hope, for I knew that I would never succeed in that one goal.

And I was jealous of him. I was jealous of his gung-ho, all-or-nothing personality. He would drink early in the morning. At night I would hear techno music blaring in his room. He would write all day and all night and then he would go out and party hard. He was a full-our worker and a full-out partier. He was extreme and radical and never let up, made no excuses, made no compromises, took no prisoners. I always wanted to be like that and never could.

You can say: "Yeah, but look, now he's dead and you're alive," but that makes no difference. He was still the kind of writer I wanted to be.

Now he is gone, disappeared behind a language barrier that will forever hide him from me. Goodbye, Mirek. I wish I could have known more of you.

Here are two excerpts - from his first two novels - taken from his website http://www.nahacz.czarne.com.pl, which was recently brought to my attention (see comment below):

From the first novel "Eighty Four" (translation Antonia Lloyd Jones):

We knew that even so one day it would all end in wives, families, homes and banal, tidy little vicious circles. One of us could land in the shit, of course, but probably not. We knew that very few people manage to end up any other way, and that those guys become legendary. We also knew that in spite of all we were just as stupid as everyone else, no different from our whole spoiled generation and that you don’t win just by talking about it. But you couldn’t win anyway, coz there was nothing to fight for. All the better, coz nowadays who’d want to anyway? Andrew was loaded, none of us was dying of starvation, nor could any of us truly say we lacked anything, or someone had abused us, our father had been an alcoholic or we’d been beaten at home. The problem was often it was an illusion of normality—in spite of all, something wasn’t quite right about this reality, some element of it was extremely fucked up. Something wasn’t working the way it should. We’re sure to grow out of it, we’ll forget, we thought. What bollocks! If nothing happens, we’ll end up fucking this planet to bits. It’s even stupid talking about it some-times, because it really does go against all logic—nothing has happened, no war like for the poets of the resistance, no regime persecuting freedom of thought like our parents had, nothing. We had something to eat, admittedly the work situation was a bit shaky, and consequently so were our future prospects, but the problem wasn’t in the shape of reality, it was inside reality itself, in its basic foundations, in its substance perhaps, I don’t know any more, maybe the Creator of the Universe fucked something up.

We were semi-aware of our hopelessness; I felt like throwing up the whole time, definitely not because of smoking, because I often gave myself a break, and anyway I smoked least of all the guys. Somehow I managed. The symptoms were like a sort of permanent downer. You don’t feel like getting up in the morning and you’re gripped by the total pointlessness of it all, then somehow you truck along, and it attacks you again. God’s played a trick on us to stop things from getting boring—he thinks to himself, “You’ve got everything OK, so I’m gonna keep fucking you up with existential fears, just so you can’t ever have heaven on earth”. And everything keeps rolling along in its own sweet way—we’ll find ourselves wives, skinny or fat, we’ll screw them a few times, they’ll have some lovely little babies, off we’ll go to work, and it’ll all fall into shape. Amen.

…It had started again, something was always starting. Someone started to say some-thing, someone started to drink something or to smoke a cigarette, someone started to stop smoking, drinking, or whatever. We could only remember the beginnings, eve-rything was always starting, and the ends were always miles away, no one ever noticed them.

The drinking never ended, the hangover just started, that’s how it was with everything. The beginning and the continuing, more and more new beginnings obscured the old endings.

Patol was filling his glass, and Andrew was waiting for someone there with a carrot-and-banana juice to kill the taste of the mushrooms. Not everyone likes them raw. You felt like saying something, words were flying around, crowding the air in the trailer, you just had to reach for them and say them. But they refused to let themselves get caught that easily—either sobriety or intoxication was needed. An in-between state didn’t re-ally do the trick. We were a bit nervy—give it here, come on, quickly, hurry up, like when you desperately want to get a present and the person hands it to you very slowly while going on about something really stupid. He was crumbling the dope, mixing it with the tobacco very slowly, way beyond any sort of hurry. It made me wonder, they all made me wonder. I once spent the night at Muko’s place; we got there pissed as farts some time aer midnight. He opened the door and we went in ever so quietly, or at least that’s what we thought. We went to bed and there was total hush. And in the morning, my God, it was like a film straight out of America, the kind with the perfect modern family, two plus one and the kid’s friend from school. So how’s it going? How’s school? More cheese on your bread? Mummy, Daddy and Muko. Something about that image grated on me, coz it stayed in my head for the next ten hours or more as he spewed along the way and paid a couple of visits to the ditch. Totally abstract. Now it’s just “yes mum, yes dad, don’t joke, don’t say more, it was great, we’re just terribly tired coz we had to help Adam clean up the cellar”.

…Patol and Andrew must have been inside by now. They were seeing things different-ly—eyes like those can’t possibly see the same way. Sitting was getting uncomfortable, the filth in the top right corner was really obvious and I couldn’t stand it any longer, I wanted to get out, to escape, I was seized with frenzy, I wanted them to stop being, talking and enjoying themselves. But I didn’t let it show, I just went on laughing.

I felt as if it wasn’t me laughing, just the shell of my body, with me inside, and it was just blocked up, something in it got jammed the moment I laughed, so I couldn’t stop. I was scared, until I saw my own frightened eyes and face, then I started looking at the rest of the guys as if they were crazy, watching what they were doing—we’re gonna kill each other any moment, they’re gonna start quarrelling and someone’s gonna pull out a hidden knife and stick it in my head, then ask “what have I done?”, but it'll be too late, with schizos there’s no joking, or we’ll go for someone, I don’t know, something’s gonna happen, something could happen, there’s too much tension that’s got to be released. And then Euzubiusz went off somewhere, and Andrew started singing a mantra, modulating his voice, and I knew it was bloody stupid, I was ashamed of my own voice, of what I was doing and how I was behaving, I was afraid Mama might hear me—what would I say to her? then I realized I wasn’t at home and no one was coming, but I couldn’t stop feeling scared, coz that’s how it works, the fear stays with you and grows; I went on singing, and the walls were shaking, I was bloody afraid, it was getting closer, it was just about to happen, something huge, the biggest thing ever, God and Satan all rolled into one, I could feel the presence on my skin and in my chest, it was huge, enormous, and we went on singing, trying to catch up with the ever escaping tune.

…Right then I’d much rather have been somewhere else. At home. I’d eat something nice and watch telly. Right through to zero hour. I could sit there forever, pitting myself against the scheduling. At about three a sign would appear on the screen to say that’s the end of broadcasting. I’d have beaten them. It’s easiest with the Polish programmes because the foreign-language ones are on round the clock. There’s always some guy blathering on, or the news, or a film. On the German channels they’re almost always screwing. What a nation of perverts. They say ordnung muss sein, but every night on TV after midnight there’s hanky panky. Das ist gut, schnella, schnella, ooo sehr gross, macht mir gut. Those silicone women squeal as if the muscular blond guys were stabbing them with metal skewers at least. So you sit and surf the channels. People on a pilgrimage click lady’s girdle ad click holy mass broadcast click gut gut ich liebe click two hundred people killed click take these tablets and your muscles will expand click one hundred and sixty wounded. I sit there clicking away—I hate television, I spend at least six hours a day hating it.

Tępy came over, chewing something. “I feel really fucked up,” he said.

Somehow it hadn’t occurred to me that he might have been poisoned. Only now. I imagined him having convulsions, losing consciousness and his skin changing colour, going completely cold and white with his mouth open. It could happen like that, like in the films, first we’d bury him, then fuck up and all kill each other, the ultimate massacre to deal with all the insinuations.

Actually I didn’t care; I could see I should be concerned, but somehow I wasn’t getting any feeling. After all, Tępy was a great guy, and I was nothing. I did worry a bit, not to be completely heartless, and then I felt calm again. I was tired and gradually I was starting to feel ill. I didn’t realise I’d already drunk several glasses; for a while I thought I’d only been drinking one, but having a sort of déjà vu. Muko kept bringing me more, like the helpful mate he is. As soon as it lit me up, I felt like puking, or rather I felt nausea. I lit a fag and thought, “I’m hungry, that helps, I must just be careful not to think too hard coz usually when we’re hungry we imagine food, and if I do that it’ll all come flying out of me.” I knew that was how it’d end, but I didn’t want to throw up just yet, at any rate I didn’t want to be first.

Everyone was talking about something, but all I could hear was a buzzing noise, like the radio in bad weather or when you’re trying to find a channel. The only way out was to throw myself into the swing of the rave, keep chatting to just about everyone without stopping, listen to the music, and for it to be thumping loud and strong, no thoughts, just dance and think about nothing but bullshit.

I got up and went to the tent, just like that, leaving them by the bonfire, without saying anything or looking at anyone. I neatly avoided the obstacles, I got knocked over once, but I tried to be tough. In the hangar-like tent I was surprised by what I saw. Tępy was lying in the corner holding his belly. I was convinced he’d stayed by the bonfire. It completely threw me off kilter. On top of that Połka was tinkering with some sort of gadget fixed to the socket and the tape recorder. He should have been by the bonfire too, not here. Połka was big and dumb, but terribly nice. He always went about in the same track suit, black with yellow stripes, and he had catarrh. I liked chatting with him because he always talked in such a funny way.

“Hi, Połka, how’s it going? what’s that you’re fiddling with?” I asked casually.

“It’s a stroboscope, but the rheostat’s fucked and won’t go for long coz it’ll blow. If I had four zlotys I’d buy a better one and it’d all be OK.”

“Isn’t it better to have it unplugged from the current? Doesn’t it fuck you some-times?”

“Eeee, no problem.”

“Great, you’re a brave guy.” I decided that was quite enough chat for now. With Połka anyway. I’d stopped feeling like talking again, but it was less of a problem now. A year ago he’d finished a professional electrician’s course, he knows his stuff. He repairs lots of things for us, walkmans and stuff like that. Połka is best mates with Todek. I don’t know him all that well, coz the way it works out I only ever see him when we’re stoned and at those times he always laughs at what I’m saying. Maybe that’s why I like him, with him I feel valued and funny.

Tępy was lying in the corner trying to say something, but for some reason he couldn’t spit out his words. Along came that so-so Heidi in the red fleece, that’s how I recognised her. She leaned over Tępy and started mothering him, saying: “What’s up, Tępy, can’t you tell me?” I immediately put in a word, telling her there was no need to worry. “He just got drunk too fast and it’s caught up with him, he feels like throwing up. I’ll help him.” I did him a good turn and didn’t let her meddle in the business with the mushrooms. Why spoil the party for others?

From the second novel "Bombel" (translation Antonia Lloyd Jones):

Pietrek’ll be here any moment and I’ll have to start talking faster to enjoy it to the full. ‘Cos I feel like saying some more, my voice sounds nice in here, bouncing off the walls of the bus stop without flying away, just drumming against the wood—it’s dry and muffled, more serious than when I speak normally. Now it’s deep, with twice the depth, like a priest saying mass, it’s inverted, vast, majestic, and partly incomprehensible. ‘Cos some-times what I say escapes me. I spout away and I’m amazed. But I’ve already said that. This voice criss-crosses itself and dissolves like the light. I noticed it ages ago. In chinks in the walls, when the sun’s shining or when a single ray falls through a knothole in the shed and reveals all the dust hanging in the air, all the tiny particles of wood, because that dust is made of wood and is tinier than anything, as tiny as air. And thanks to the knothole, thanks to the chinks I know light dissolves in straight lines. Just like my voice is doing now. Only when I get drunk it all goes bent, it doesn’t break off, well, maybe sometimes it does, but usually it bends like rubber or lino.

What’s up? Pietrek should be here by now, and I guess I’m sweating and feeling sick at the thought he might not come, ‘cos come to think about it, where exactly did I get the idea he was going to come so early? I’ve persuaded myself to go on sitting here, freezing and hoping. ‘Cos why should he come? I’ve got it all in a muddle.

It’d be best if he came before eight, before the bus comes. And then, if we’re lucky, maybe some guardian angel of mine might just be thinking, “Poor old Bombel, he’s had an awful life, his mother didn’t love him, his father used to beat him, and his wife turned out to be a whore—his whole life’s been bad luck, so I’ll do something good for him, ‘cos actually I’ve never really been bothered about him, just this one time I’ll make sure he has a good driver, who out of Christian goodness will turn a blind eye to his lack of a ticket”. And everything’ll be absolutely fine. We get into the bus, me and Pietrek, modest, but proud, good morning, good morning, what a nice day it is, yes, it is, just a bit too cloudy, then we sit down, with two nicely turned-out women in front of us; I tell them they’ve got a nice, choice bouquet of shampoo and deodorant, to which they say thank you and ask if they can sit on my knees because I’m so polite. The driver turns on some soft music, everyone’s smiling, it’s wonderful and no one’s bothered that we haven’t got tickets. It could be like that.

Worse if the bastard feels as if something depends on him, then he’ll remember he’s got a big fat wife with massive buttocks waiting for him at home—each of those enormous cheeks is like a whole separate arse—all hope of any sort of subtle sexual nuance is off the agenda from the very start, all because of that fat, which is a better defence than an iron chastity belt. And maybe it’d be all right if he couldn’t see women sent straight from heaven at every step, ‘cos these days they’re everywhere: on posters, in the papers, on telly and in calendars. And then the poor old driver thinks he’s got the biggest fatty in the world, he’s the worst off of anyone, he’s got to deal with the devil, and when he remembers all that, that great sonofabitch of a bus driver, that lord and master, that lord over life and death, that moustachioed image of destiny, then he’ll ask: “So where’s your ticket? Got a season ticket? sell you one?”, and the joker can see he’s not dealing with millionaires.

But if everything went according to my plan, we could go down to the border and buy some cheap alcohol, cheap vodka, ‘cos Pietrek’s supposed to be bringing a bit of cash, and if not vodka, maybe wine, ‘cos it’s cheaper, better and there’s more of it.

We can cross the state border now, it’s all sorted now, it’s allowed by law, we’ve got passports and everything. It’s a year since zero hour went by, fucking hell, there was so much happening then, the very thought of it makes me want to part-laugh, part-cry, in both cases with a touch of fear thrown in. Something immediately tempts me to tell myself about it, hear it all from the beginning, via the middle, right through to the end. But it was already a long time ago, a year is a long time ago, half a year isn’t, but a whole twelve months, with so many seasons in between, that’s so much time I’m amazed you can remember something for such an age. But if the days are all alike, if in all that time only the outside look of things changes, the temperature and all the other variables, it’s hard to remember anything, ‘cos it all merges together. If you spend a day drinking, then a second, a third and all the days after that too, after a while you remember the whole lot like one single day.

But I’ll always remember that outing with Pietrek, whether it was a whole lot of days or not, merging together or not. To this day whenever I see anyone darker, with browner skin quite literally speaking, I get the creeps and start looking round in case there are more of them, in case there’s one of Hitler’s secret weapons hidden in the bushes, some artillery back-up, five Gypsy ragamuffins with knives, sticks and fuck knows what other home-made weaponry. ‘Cos you never know what’s going on with darkies. My mother was wise to scare me with the Gypsies when I was still in nappies, ‘cos to this day I’ve been le with a sort of caution, a sort of instinct that tells me to watch out for darkies, so if one appears in the corner of my eye at once a red light goes on in my head to give the full alert, bells ring and I’m on my guard. Sometimes they come to the village to sell a carpet which, fuck it all, I’d bet my right hand or a bottle of wine they knocked off in some other village far away from us so word wouldn’t get round. But it gets round any-way, ‘cos they’re darkies, Gypsies, someone called them that, didn’t they? Except they’ve got hot chicks—if I had one of those Gypsy birds with the coal-black hair I’d use her properly, the way nature intended; she wouldn’t have to do a thing for me in the kitchen, I’d even do the cooking, washing and cleaning myself. I’d tie her to the bed, but not by the hands, ‘cos they’d come in very useful. But getting back to what I was talking about, they come along with that carpet, to our village, they say they’re looking for a buyer, they say this and that, it’s nice and cheap, it’s a real bargain, lady, so you think about it; on top of the carpet they’ll chuck in a ring made of stainless gold for free, so you think some more, and finally you say no, and you mean no, end of story, you don’t have to explain yourself to the Gypsies, do you? So they say they’re going now, but they’re lingering, saying lady, lady, why not buy the carpet—the opportunity won’t repeat itself… fucking right, you can be sure it won’t, ‘cos the owners won’t let their carpet get nicked a second time. So finally they leave; the house was full of people, children, the husband, daughter-in-law, brother-in-law, grandchildren, the neighbour over for coffee, and then it turns out the gold chains have gone, the ones the kids got for their first holy communion and first confession in one—just as holy or even more so, ‘cos without the one you couldn’t have the other—those chains were hidden in the sideboard. Sometimes the TV’s gone—the moment no one was watching it they took it away, or it’s a man’s leather jacket that’s gone, or other valuable crap like that.

Τηεψ ωερε ηερε βεφορε τηε ωαρ τοο, σομε οφ τηεμ φορ γοοδ, Ι δον τ κνοω φορ συρε χοσ Ι δον τ ρεμεμβερ, Ι ωασ τοο ψουνγ. Ι σαιδ εαρλιερ ηοω ολδ Ι αμ, ωηιχη σηοωσ Ι χουλδν τ ηαϖε σεεν ιτ μψσελφ ανδ δον τ κνοω ωηατ ιτ ωασ αλλ λικε βεφορε τηε ωαρ. Σομεονε τολδ με αβουτ τηεμ—maybe the Captain was bemoaning their fate when he was drunk, ‘cos even though they’re darkies, even if I hate them and I’d immediately kick out any of them who came into my yard without a by your leave, the main thing is not to exaggerate. What’s happened to them is nothing but weeping and wailing.

Sometimes when I’m drunk I feel pity for the lot of them welling up inside me, tears squirt from my eyes unasked for, then all you can do is huddle up to a mate and cry on his shoulder, with all the darkies before your eyes, all the people who used to be alive but aren’t any more.